The Canterbury Tales was written in around 1400 CE by Jeffrey Chaucer. This is a collection of 24 stories of valor and ineptitude; religion and sacrilege; romance and ribaldry. It was written in Middle English. Importantly, the Canterbury Tales was one of the first widely-popular works to be published in English. In contrast, most (but not all) contemporary work was published in French, Italian, or Latin. Thus, some scholars call Chaucer the father of English literature. To a modern reader, Chaucer’s work is fascinating for linguistic reasons, among many others. This ancispeakent work offers a window into the evolution of modern English.

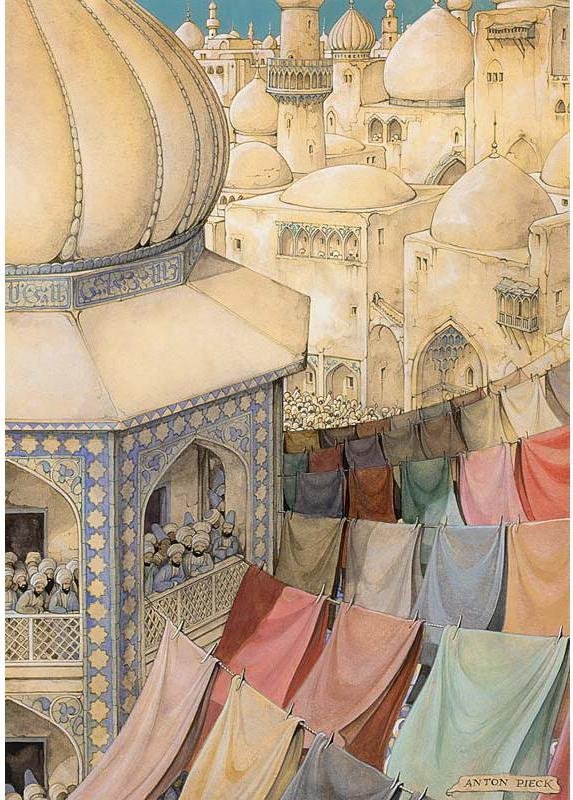

The first, and perhaps the most important, tale within the Canterbury Tales is The Knight’s Tale. The Knight’s Tale was actually adapted from the epic poem Teseida (full title Teseida delle Nozze d’Emilia, or The Theseid, Concerning the Nuptials of Emily) by Giovanni Boccaccio. The Knight’s Tale, among other works by Chaucer, is part of the Matter of Rome, a literary cycle which concerns Greek and Roman mythology. In particular, The Knight’s Tale concerns the Greek hero Theseus, and the rivalry between the two knights and cousins Palamon and Arcite, who both vie for the affection of Theseus’s beautiful daughter, Emelye. The Knight’s Tale was later adapted by Shakespeare in his play The Two Noble Kinsman.

Theseus becomes aware of the rivalry between the two intrepid knights for the love of his daughter. In order to resolve the dispute, he proposes that both Arcite and Palamon assemble and command armies, and arranges for a grand public battle between these armies. The winner will marry Emelye. However, he seeks to reduce the amount of needless death and destruction. Therefore, immediately prior to the fight, he commands that the armies may use blunt but not sharp instruments, and that any soldier, after having been wounded, should be taken to the sidelines to recover, rather than be killed. At this:

The voys of peple touched the hevene,

So loude cride they with mery stevene,

“God save swich a lord, that is so good:

He wilneth no destruccioun of blood!”

Up goon the trompes and the melodye

And to the listes rit the companye

By ordinaunce, thurghout the citee large

Hanged with cloth of gold, and nat with sarge.

The people’s voice reached the heavens,

So loud they cried out with joyful voice,

“God save such a lord, who is so good;

He wills that there be no loss of blood!”

Up start the trumpets and the music,

And the company rides to the lists

In order through the large city,

Which was hung with cloth of gold, not with dark serge.

Upon first reading his decree, which established strict rules around the fight, I didn’t know how to react. Were such provisos typical of battle at that time? Would people be upset at being denied a real fight, in all its brutality? I was then delighted to read that, at Theseus’s proclamation, The voys of peple touched the hevene, and Up goon the trompes and the melodye. Chaucer seems to be quite deliberate, not just in describing Theseus’s declaration, but in describing the response to it. The response is perhaps as important as the declaration itself. That the response among the people is positive, and includes pomp and circumstance, lends a special sort of legitimacy to the declaration. The response to the declaration, including the ritual that ensues, effaces doubt, and creates a sense of correctness or rightness surrounding the state of things.

Continue reading